A new direction for the theory of action

Western Marxism and the « philosophy of praxis »

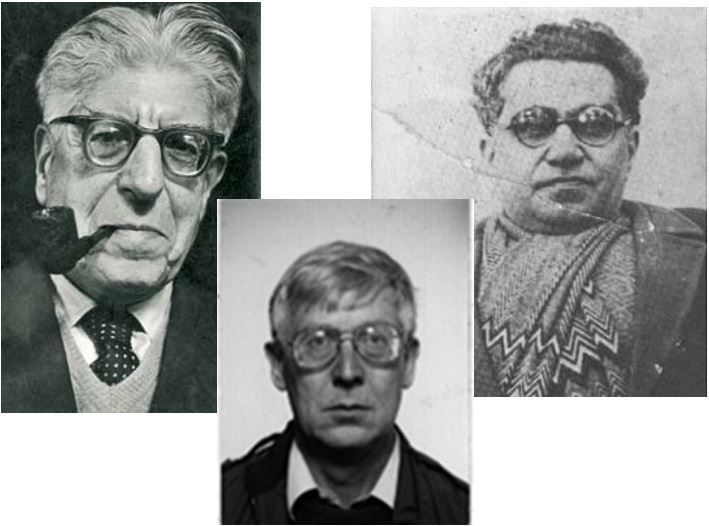

(Perry Anderson, Ernst Bloch, Antonio Gramsci, etc.)

*

Robert Kurz

In the left wing critique of capitalism expressed in the second half of the 20th century (there were rudimentary versions of this critique ever since the inter-war period), a split took place, or at least a differentiation, which was much more important than the ostensible schism in party-Marxism between social democracy and the Bolsheviks. For the global periphery, the process of “catch-up modernization” remained the determinant factor right up to its collapse in the Third Industrial Revolution. The contradictions of the “real socialism” of the East and of the development regimes of “national liberation” in the countries of the South were justified on the ideological level by the traditional ideas of transformation of the “workers parties” that had become States. Dogmatically paralyzed Marxism-Leninism was falling apart under the pressure of the economic praxis of the “laws” of modern commodity production and of the world market, resorting to a series of technocratic concessions to the logic and the dynamic of the real, unsuperseded capitalist categories, until the ideological façade suddenly went up in smoke in the turning point of 1989. Almost overnight, the fake Marxist-Leninist dogmatists changed sides, becoming equally dogmatic neoliberals, on the terrain of collapsing mafia regimes amidst the desolate landscapes of “catch-up modernization”.

In the highly developed capitalist countries of the West, on the other hand, the impulse of modernization of the traditional workers movement had already begun to run out of steam after the First World War. Then, after its defeat at the hands of fascism and National Socialism, it experienced a total demoralization with regard to its respective ideas of transformation. In post-war Fordism, the function of modernization was then largely transferred from the traditional workers movement and its party apparatus to the Keynesian regulatory State, in which trade unions and workers parties were corporatively integrated, now deprived of their role as historical vanguard. Social democracy was transformed into a system of “people’s” parties, party-communism was social-democratized, and the representatives of the paradigm of party-Marxism by and large became part of the “political class” of the commodity-producing patriarchy.

The erosion of party-Marxism therefore took place in a way that was very different in the real socialism of the East and South as opposed to the way it happened in the West. The “socialist” (State Capitalist) regimes of “catch-up modernization”, which had only recently imposed “abstract labor” and the modern relations of “value-dissociation” on their societies, had to struggle, over the course of this long process, with the contradictions of an unsuperseded “political economy”. For this reason, their treatment of the specific contradiction was up to the very end still bound up with that metaphysics of law-governed structure, with characteristics that were almost those of natural science, and measured by the theory of structure (in the broadest sense of the term outlined above), in such a way that these countries, consequently, ended up, “in accordance with the laws”, in the capitalism of global crisis. In the Western countries, however, “abstract labor” and the relations of value-dissociation have long since become the “natural basis” of society; since their origins, the functions of the “catch-up modernization” of the workers movement and of party-Marxism have in the West been limited to the juridical-political level of the treatment of the contradiction, in the sense of the “struggle for recognition” (including the fields of action in the trade unions and in the Welfare State); that is, they were reduced, in the truncated and mechanistic terminology of historical materialism, to the “superstructure”. And it was along those same lines that the process of ideological erosion also took place in the West.

During the process of the extinction of the function of internal modernization in the wake of the First World War, an ideological formation known as Western Marxism developed, at first only in the domain of collapsing party-Marxism. Despite all its internal distinctions and differences, which we cannot discuss in detail here, there is a common trait that all its representatives share. For the English Marxist Perry Anderson, as he observes in his essay on the topic, this was “… the studied silence of Western Marxism in those areas most central to the classical traditions of historical materialism….” (Anderson 1978, 1st Ed. in English 1976, p. 71). First of all, he mentions the “scrutiny of the economic laws of motion of the capitalist mode of production” (ibid.).

In fact, Western Marxism displayed a tendency to gradually abandon the critique of political economy in the strict sense of the term. After the epoch of the world wars and the world economic crisis of the 1930s, the great Marxist debates concerning the theory of accumulation and of crisis, the “economic theory” of transformation and of socialism/communism, came to an end; all that remained of these questions were sporadic rearguard confrontations without any great importance. This development was accompanied externally by the Fordist prosperity of the post-war years in the West, which pushed such questions to a secondary level. This ideological tendency to downplay the theory of accumulation and crisis is still active today, in the world crisis of the Third Industrial Revolution, as the “belief” of the left in the immanent capacity of capitalism for eternal existence. Naturally, the appalling development of “real socialism”, including its collapse, also helped to discredit the old paradigms.

The surreptitious abandonment of the “hard” political-economic questions and consequently of the problematic of the basic social form in general was consistent, above all, with the internal logic of the Western Marxism of modernization itself, in its limitation to the juridical-political sphere of the treatment of the contradiction, in whose domain its truncated understanding of the critique of political economy is also inscribed. Then there was also the failure of the “revolution” in the West which, in this sense, was deprived of any object. There were no criteria for revolution that could envision the transformation of an already highly developed system of “abstract labor” in the context of the paradigm of immanent modernization, that is, of the treatment of the contradiction in the sense of the ideology of the class struggle.

The new direction taken by Western Marxism was prepared by and based upon the so-called “philosophy of praxis”, also known as “thought of praxis”, “concept of praxis” or “theory of praxis”; a concept that is represented, in different aspects, principally by Ernst Bloch and Antonio Gramsci, and which was pursued in a multifaceted way. First of all, in a quite traditional Marxist way, “philosophy of praxis” meant demanding as an object of theoretical elaboration, in external opposition to a merely “historical-intellectual” reflection, “real” or “material” relations of life and of reproduction, in pursuit of practical intervention. This is, of course, an unavoidable understanding of “historical materialism”, formulated in detail by Marx and Engels in The German Ideology. It should also be noted that the latter work constitutes, together with the “Theses on Feuerbach”, the central reference of the philosophers of praxis. In this way, however, the fetishistic constitution of the “real” praxis of life or “sensuous human activity” (“Theses on Feuerbach”) was completely obscured, whose concept was, furthermore, absent from The German Ideology and only emerged in Marx’s work with Capital and its preparatory materials. As a result, similar to what took place with respect to classical party-Marxism, Western Marxism also failed to clarify or else misunderstood the “Theses on Feuerbach”, and non-critically hypostatized “sensuous human activity” and established “praxis” as an indeterminate field par excellence.

What, however, was really new in the “philosophy of praxis” of Western Marxism? With its specific interpretation of the “Theses on Feuerbach” and The German Ideology, the philosophy of praxis was intended to derive a new paradigm from the concept of praxis. The Marxian theory in the broadest sense was manifested in this case at a very high level of abstraction as the “philosophy of praxis” (of social action) par excellence, one whose character had previously been misinterpreted. An essential aspect of the new interpretation was the understanding that action had to be freed from the determinism that had previously dominated it. Gramsci, for example, expresses this point in his Prison Notebooks: “We should, I think, prepare a funeral elegy on the concept of fatalism…. The fading away of ‘fatalism’ and ‘mechanicism’ marks a great historical turning-point” (Gramsci 1994, 1st Italian Ed. 1975, written in 1932/35, p. 1392 et seq.). This implies a proclamation of a movement of disengagement on the part of Western Marxism with relation to the metaphysics of law-governed structure that was previously dominant. The problem of law-governed structures affecting social development, however, was not transformed into the categorical critique of the historical fetishistic constitution, but was put on the shelf. Instead, the concept of “praxis” then enjoyed a whole new career, which resulted in a totally illusory and particularly affirmative transformation of traditional Marxist thought.

For the new understanding, the concept of “economism” became crucial. In the view of the “philosophers of praxis”, the Marxism of the past had placed an exaggerated mechanistic emphasis on the determinant role of the “economy”. This critique, however, was linked with the abandonment of the critique of political economy in the strict sense, which was subsequently verified by Perry Anderson (who, for his part, supported a more traditional argument). It really is possible to connect classical Marxist “economism” with the idea that the development of the accumulation of capital was mistakenly understood as direct historical determinism, in its relation with the empirical “economy” and, usually, complemented by the “class struggle” associated with it. Engels had already attempted to correct this mechanistic economism, by determining “the (objective) economy” as a “factor” that was only determinant “in the last instance”, but which was modified and transformed in the real forms of development, by way of (subjective) political, ideological and cultural occurrences, etc. This correction, however, was hardly profound and shared the false assumptions of its predecessor. This was due mainly to the fact that the problem of the modern fetishist constitution remained, for Engels, a book sealed with seven seals. This is why he also had to fail with respect to the critique of “economic” determination, in his attempt to soften and modify the unchallenged metaphysics of law-governed structures merely with high-sounding rhetoric about economic determination “in the last instance”.

From the perspective of the critique of the fetishistic a priori matrix, a critique that is linked with the “other” Marx, the critique of classical economism must be viewed in a totally different way. It is not the “economy” or even the “class struggle” associated with it that is important, not directly and not in the last instance, either. Instead, “conformity with the law” is, in the a priori matrix of the real metaphysics of modernity and of the context of its form, a matrix that serves as the basis for all actions in capitalism, including its treatment of the contradiction, and is always reproduced in this action (commodity form and gender dissociation, and the corresponding identity of form of thought, form of action, subject form, form of theory, form of politics, etc., as forms of reproduction). This constitution has deeper roots than all empirical (and also institutional) movements and development “within” its context. There is no point in wanting to transform the problem into the mutual influence and interpenetration of diverse “relatively autonomous” spheres, or of “partial systems or subsystems” (to use the terminology of systems theory). The concept of the totality, of the social totality, then becomes the mere “sum” of these spheres or partial zones; the concept of “system” is hollowed out and represents only a rhetorical device.

The definition of the “economy” as determinant—regardless of whether it is directly determinant or only “in the last instance”—is a completely truncated and mutilated formulation of the problem and remains a-conceptual. Value-dissociation constitutes a broad, basic real category, from which, and only from which, that structural “complete differentiation” can be allocated with its “relatively autonomous” social spheres. “The economy” in the empirical sense does not determine, but is itself determined by the overarching a priori matrix of the fetishist constitution and by its “logic”, which produces a “law-governed structure” according to a pattern that is almost identical to that of the bees (and also within the “economy”). The adequate critique of this “law-governed structure” can only be constituted by negating the mode of socialization as such, which implies the dualism that exists between “economy” and “politics” in general, and which is also linked to gender dissociation.

The truncated critique of “economism” carried out by the philosophy of praxis also shares, just like Engels, the same mistaken assumption; that is why we hear repeated references to the formulation by Engels concerning the “relative autonomy” of the spheres or partial domains of capitalist socialization which, as such and in their mutual connections, ended up gradually disappearing from sight. For this reason, the “new thought” of the philosophers of praxis did not provoke a more comprehensive and more profound critique of the a priori matrix of the fetishistic constitution via the critique of the metaphysics of law-governed structures and of classical “economism”. Instead, it distanced itself from that critique, and moved for the most part in another direction entirely, in the direction of the current of the theory of action of bourgeois ideology.

It was this fundamental turning point for the theory of action, in which the debates initiated by Western Marxism or by the philosophers of praxis concerning the analysis of the “economic laws of motion of the capitalist mode of production” yielded to an emphasis on the “subject”, or the celebrated “subjective factor”, in connection with the questioning of the theory of culture and the theory of knowledge and/or epistemology. The positivism of the metaphysics of law-governed structures, derived from the paradigm of the natural sciences, was only replaced by the positivism of a metaphysics of the will and of intentionality (adapted by the philosophers of praxis to the sociology of classes), a positivism that was drawn from historicism, vitalism or phenomenology and/or existentialism. Thus, roughly speaking, instead of the execution of historical law-governed structural mandates, there was henceforth will versus will, instead of action in conformance with “laws”, there was action against and despite “laws”, but in the same constitution of the a priori matrix of the still-intact and completely unreflected-upon fetishistic relations. “Bees” have always been “architects” after all, only with different ideas—ideas whose origins remain obscure.

Thus, light is also shed on the erosion that took place, with totally different results, in the party-Marxism of the real socialisms of the East and the South, which ended up collapsing, and in the West. Whereas in the East and the South, “socialist intentionality” pursued with ever mounting efforts the establishment of the non-superseded a priori matrix, aiming at surrendering to the “law-governed structure” of the latter, in the West the turn taken by the theory of action towards “praxis” involved self-deception with regard to the nature of the problem. This was only possible because Western Marxism did not find itself under the pressure of an allegedly real transformation (actually a “catch-up” implementation of relations of value-dissociation) and no longer by any means faced the problem of transformation at all, but instead began to lose its way in the treatment of the contradiction and in the real interpretation of capitalism, on the basis of a highly developed formation of “abstract labor” and the socialization of value-dissociation. Thus, the dichotomous internal opposition of the ideology of bourgeois social theory was reproduced in Western Marxism only as the transition towards the other pole, the pole of the theory of action.

Characteristically, Gramsci designated the October Revolution, in a famous formulation, as a “revolution against Marx’s Capital”. He did so without any critical intention, but rather only in the sense of an alleged “triumph of the will”, understood in the light of the theory of action, over the metaphysics of law-governed structure and “economic mechanicism”. The ensuing contradictions of development of real socialism were of little interest to him; what he was interested in was above all the revolutionary subversion that seemingly attained the level of relations of power in the “class struggle” (despite and also against the “laws”), while the question of basic social forms began to be set aside, as they were perceived only in the sense of juridical-political “institutions”.

The non-critical and unmediated formula of the “inseparable unity” between “theory and praxis”, which could always only lead to the connection with the ontologized patterns of action of the a priori matrix, was supposed to be reproduced immediately; but now in the version of the theory of action of the metaphysics of intentionality. Thus, Gramsci also postulated the “energetic reinforcement of a unity between theory and praxis” (Gramsci 1994, 1st Italian Ed. of 1975, written in 1932/35, p. 1282). We find a similar formulation in Ernst Bloch’s The Principle of Hope, concerning the “Theses on Feuerbach”: “Thus, the right thought and doing what is right finally become one and the same” (Bloch 1968, 1st Ed. 1954-59, p. 83). It is true that Bloch, in his reflections on the “Theses on Feuerbach”, turned against the pragmatic-practical interpretation of a “pseudo-active self-confidence” (ibid., p. 87), in this sense reminiscent of Adorno, and sought to demarcate the Marxist relation between theory and praxis from a bourgeois understanding restricted “… to mere ‘application’ of theory” (ibid., p. 83). He did not thereby attempt to criticize the connection of theory with a pre-established, ontologized praxis, but rather the contrary: bourgeois theory, according to Bloch, “… only condescended to ‘application’ to practice, like a prince to his people, at best like an idea to its utilization” (ibid., p. 83). As a criterion, however, utilization already points precisely to the subordination of theory to an ontologically pre-established, unexamined, goal, and not to its “bourgeois arrogance”, as Bloch wanted to suggest. If theory, as Bloch understands it, must not “condescend” to stoop to praxis, then he is saying that theory, inversely, must be based on praxis (on the class struggle reformulated in the light of the theory of action), rather than that it needs to distance itself in relation to the treatment of the immanent contradiction. By compelling theory, in this case, to take on the “partiality of the revolutionary class standpoint” (ibid., p. 90) and by celebrating Marx’s “major work” as “a clear directive for action” (ibid., p. 95), his own understanding of theory is already found in a “horizon of use” of instrumental reason, whose fetishistic constitution remains entirely unexamined.

It is thus rendered impossible to attain either a critical concept of the “form of theory”, as the bourgeois “form” of “reified consciousness”, or a critique of the legitimizing reference and real interpretation linked to that form, as such a reference is already found per se established in each and every postulate of an a priori “unity” between “theory and praxis”, and it is even less possible to attain a postulate modeled in accordance with the theory of action. For this reason, like the traditional party-Marxism, the philosophers of praxis are still incapable of going beyond the difference between the dominant (fetishistic) praxis of life, the particular “counterpraxis” as the treatment of the contradiction in the field of capitalist immanence, and the transcendent praxis that goes beyond this (by shattering the constitutive connection of the form). It is clear that in this way the concept of critique cannot be separated from its immanent content, either, a content inherited from the history of the imposition of capitalism, in order to be transformed into a categorical critique. More than ever before, theory remains “imprisoned” in the treatment of the immanent contradiction, only now in the turn towards the theory of action. Praxis is praxis is praxis….

Naturally, the metaphysics of labor, as the ontology of labor, is in this case prolonged without any interruption, as Bloch observes when he refers to Marx, the theoretician of modernization in the understanding of the workers movement, and after defining the bourgeois ontology of labor from Hobbes to Hegel, as a “first stage” of a “merely contemplative materialism” or of an “objective idealism”: “At the same time Marx of course makes it clear that bourgeois activity is still not the complete, right (!) kind. It cannot be so precisely because it is only appearance of work, because the production of value never emanates from the entrepreneur, but from peasants, manual workers, ultimately wage-earners” (Bloch, ibid., p. 67, Bloch’s italics). His candor is impressive, the way the obvious problem of a common ontology of labor in Modernity, which indicates the fact that the Marxism of the workers movement is part of the bourgeois form, is reinterpreted to identify the apparent difference that the bourgeois ontology of labor was not “right”. For Bloch, just as for traditional Marxism, the “real” metaphysics of labor, the one that is supposed to supersede the “appearance of work”, will only result from its identification with the “[real] production of value” on the part of the dependents; we should note in passing that an ontology of the form of value is also introduced that is even extended to all (pre-modern) peasants and manual workers.

However, Bloch’s ontology of labor does not imply any recourse to the critique of political economy, neither with regard to the theory of accumulation and/or crisis, nor with regard to the problematic of social transformation, where the metaphysics of the law-governed structure of traditional Marxism made such great efforts only to end up failing in “real socialism” (in any event, it failed with respect to its pretense to be a supersession of capitalism). The ontology of labor now disguises itself in a historically indeterminate, generalized, expanded ontology of praxis, which is adapted to the theory of action and on the basis of which the a priori matrix of the fetishistic constitution is systematically disregarded. For the problematic of transformation, to the extent that it even arises, this entails, in a way, the relapse into utopian thought. More than ever before, the relation of immanence and transcendence, which evades the question of the contradictions of the ontology of labor, remains indeterminate and falls apart in the nebulous expressions of “utopianism” (Bloch). The question of a real supersession of the capitalist fetishistic constitution is thus aborted all the more definitively once an allegedly transcendent “utopian” content makes it possible to find hidden meanings in the limited “counterpraxis” of the treatment of the immanent contradiction, before praxis reaches the threshold of a categorical critique. This is why the so-called “concrete utopian” concepts preferred by the philosophers of praxis of different tendencies necessarily become bogged down in inessential particular factors, which do not even come close to scratching the surface of the capitalist modes of socialization, or else the fetishist forms of this modus must be reinterpreted or “redefined” in a way that makes them seem beneficial for human beings. Thus, the utopian “concrete” is either always the orientation for a socially irrelevant action in the interstices of the capitalist real abstraction, or else the latter must be disguised in various illusory vestments.

The relapse into a diffuse utopianism, however, a utopianism that is overflowing with sentimental metaphors (in the mobilization of the concept of “Heimat” [homeland] in Bloch, for example), is only one aspect of the turn towards the theory of action. Of greater and much more enduring importance is the reinterpretation (instead of supersession) of Marxist politicism that accompanied this tendency. The connection of the “theory form”, its bourgeois nature not being understood, to the immanent treatment of the contradiction led, as everyone knows, to its integration into the equally bourgeois “political form”; and among the philosophers of praxis this also immediately meant continued involvement in party politics. However, on the basis of the turn towards the theory of action and in the context of the truncated critique of “economism”, an extension or an inflation, or in a manner of speaking, an autonomization of the concept of politics took place, such as is announced in Gramsci: “In this way we arrive also at the equality of, or equation between, ‘philosophy and politics’, thought and action, that is, at a philosophy of praxis. Everything is political, even philosophy or philosophies … and the only ‘philosophy’ is history in action, that is, life itself” (Gramsci 1992, 1st Italian Ed. 1975, written in 1930/31, p. 892). Already in this terminology we can discern a certain dependence on the thought of vitalism, on whose horizons the concepts of The German Ideology are interpreted. The direct “equation between … thought and action” (actually, the “binding” of theory in the a priori negative identity of the form of thought with the form of action) must transform reflection directly into “history in action”, observing that the words, “life itself” take the place of the critique of the social constitution. The key announcement is: “everything is political”.

With this the decisive difference between Gramsci’s view and the still-prevalent party-Marxism of the framework of the metaphysics of law-governed structures becomes obvious. In the understanding of party-Marxism, politics was by no means “everything”, but rather was itself a “means to an end”, to which theory, for its part, is once again subordinated in an instrumentally legitimizing way. The “end” must consist in the “historically necessary” (determined) transformation “in accordance with law” in a “socialistically planned” reproduction. However, since this goal still falls short of the threshold of the categorical critique and still ontologically presupposes capitalist forms, it must arise in the illusory proclamation of a power of command exercised by “socialist” and/or “proletarian” politics and nationalization in the context of the positivistically affirmed form. Despite, or precisely because of, this imperative, a distinction of content continued to exist between politics and social transformation, between means and end. In the sense of an emancipatory supersession of the modern fetishistic constitution, it was an unviable means to an unviable end, only explicable on the basis of the constellation of “catch-up modernization”. Even so, when Western Marxism took its turn towards the theory of action and thus eliminated all questioning, which was drowned in the truncated critique of “economism”, all that remained was politics, so to speak, “left high and dry”. The formula “everything is political” shows the political “means” transformed into its own “end”, and thus the presupposed end-in-itself of the “automatic subject” is obscured and concealed, even more than in the truncated understanding of traditional Marxism.

Thus, the turn towards the theory of action uprooted traditional Marxist politicism from its anchorage in the problematic of accumulation, crisis and transformation, in order to hypostatize its politicism more than ever before. The a-conceptual contrivance of the economic “last instance” was no longer anything but a mere decoration, and definitively ceased to be taken seriously in the context of the basic social form and was transformed into mere ontological background noise. All that remained was the emphasis on the “relative autonomy” (which soon became an overused catchphrase) of the spheres, partial areas and social subsystems, culture, etc., and especially politics. This inflated concept of politics became tautological, and even autistic. In short, it was no longer possible to inquire as to what the goal of a social supersession of capitalism really should contain; the determination of the content was totally replaced by a metaphysics of the will and of intentionality based on the theory of action. This really absurd understanding was fatally assimilated to the Heideggerian metaphysics of “determination”, so often the target of ridicule: “we are being obscurely determined, only we do not know into what”. Politics is politics is politics….

This is why we also notice in Gramsci, for example, the above mentioned sweeping lack of concern with the contradictions of the Soviet state-bureaucratic “planned society” (which, in any case, were perceived from the perspective of a superficial democratism, without noting the paradox of a “planning of value”), and the restriction of interest to revolutionizing political relations in the broadest sense of the word. “Everything is political” also meant: everything is a “power relation”, or a “relation of forces”, even to the very deepest recesses of society. The fetishistic content of power, the “automatic subject” of the valorization of value, “abstract labor” and the relation of gender dissociation, that is, the context of the social form, as the content on the basis of which power in general is generated, is therefore completely ignored. The traditional sociology of “classes”, which still possessed a positivistically reduced relation with the problematic of the form, was now totally released and “disconnected” from that problematic. The metaphysics of intentionality of the theory of action dissolved sociability in general into relations of will; therefore, will against will, as “class against class” and as the infinite reconfiguration of the “relations of forces”, without the assumptions of the constitution of the form and without the goal of a break with that constitution.

In this context, Gramsci invented a very powerful concept of “hegemony”, or of the eternal struggle for hegemony, which incorporated the common fetishist form of the will and thus the concept of the capitalist relation, as well as the concept of praxis: “Consciousness of being part of a particular hegemonic force (that is to say, political consciousness) is the first stage towards a further progressive self-consciousness in which theory and practice will finally be one…. This is why it must be stressed that the political development of the concept of hegemony represents a great philosophical advance as well as a politico-practical one. For it necessarily involves and supposes an intellectual unity….” (Gramsci 1994, 1st Italian Ed. 1975, written in 1932/35, p. 1384). Consciousness in general and critique in general become pure “political consciousness” stripped of their conditioning. Whereas in “real socialism” politics was gradually receding before the pseudo-natural laws of the fetishist constitution, so as to finally unconditionally surrender to them, precisely the opposite happened in Western Marxism, in which the same unsuperseded social constitution was ideologically shattered into pieces in “politics”, while systematically ignoring the de facto fatal development of real socialism. The proclaimed “unity between theory and praxis” under the formula, “everything is political” of the theory of action was transformed into the slogan, “politics is everything”. Consequently, more than ever before, theory was degraded to the status of a legitimizing theory of a “political praxis”—an a priori presupposition for theory—of the immanent treatment of the contradiction, but now involving a politics uprooted from its anchorage in the constellation of “catch-up modernization” that now had no reason to exist, a politics that was transformed into the historical zero-point of eternal “struggles” in the eternal parallelogram of “relations of forces”. Actually, this was also a surrender, but a vacillating one, negated and fake: an implicit self-compromise with the definitively obscured modern fetishistic constitution, notwithstanding the bellows and roars issuing from the chest of the “consciousness of struggle”, in which the puffed up chest of the proletarian class can only display itself as a chicken breast. Struggles are struggles are struggles…

Originally published under the title : “Grau ist des Lebens goldner Baum und grün die Theorie. Das Praxis-Problem als Evergreen verkürzter Gesellschaftskritik und die Geschichte der Linken”, in EXIT! Krise und Kritik der Warengesellschaft, No. 4, 2007 (ISBN: 978-3-89502-230-2, Horlemann Verlag, Postfach 1307, 53583 Bad Honnef, http://www.horlemann-verlag.de/).

- Anderson, Perry (1978, 1st English language Edition 1976): Uber den westlichen Marxismus, Frankfurt am Main. [Considerations on Western Marxism]

- Bloch, Ernst (1968, 1st Ed. 1954-59): Weltveränderung oder die elf Thesen von Marx uber Feuerbach [The Transformation of the World or Marx’s Eleven “Theses on Feuerbach”], an excerpt from the book, Das Prinzip Hoffnung [The Principle of Hope], in Uber Karl Marx [On Karl Marx], Frankfurt am Main.

- Gramsci, Antonio (1992, 1st Italian Ed. 1975, written in 1930/31): Gefängnishefte, Vol. 4, Hamburg. [Prison Notebooks]

- Gramsci, Antonio (1994, 1st Italian Ed. 1975, written in 1932/35): Gefängnishefte, Vol. 6, Hamburg.

Other texts :

- We are everything. The misery of (post-)operaism (Robert Kurz)

- Foucault's pendulum. From party-Marxism to movement ideology (Robert Kurz).

- "Structuralist Marxism" and the politicism of the theory of action (Robert Kurz)

- A new direction for the direction of action.Western Marxism and the « philosophy of praxis » (Perry Anderson, Ernst Bloch, Antonio Gramsci, & cie), by Robrt Kurz.

/image%2F1488848%2F20161113%2Fob_e27604_screen-shot-2011-11-08-at-22-20-58.png)